This is the first of a two-part series on the new era of financial warfare

It was the third day of the war in Ukraine, and on the 13th floor of the European Commission’s headquarters Ursula von der Leyen had hit an obstacle.

The commission president had spent the entire Saturday working the phones in her office in Brussels, seeking consensus among western governments for the most far-reaching and punishing set of financial and economic sanctions ever levelled at an adversary.

A deal was close but, in Washington, Treasury secretary Janet Yellen was still reviewing the details of the most dramatic and market-sensitive measure — sanctioning the Russian central bank itself. The US had been the driving force behind the sanctions push. But as Yellen pored over the fine print, the Europeans, worried that the Russians might get wind of the plans, were anxious to push the plans over the finishing line as quickly as possible.

Von der Leyen called Mario Draghi, Italian prime minister, and asked him to thrash the details out directly with Yellen. “We were all waiting around, asking, ‘What’s taking so long?’” recalls an EU official. “Then the answer came: Draghi has to work his magic on Yellen.” By the evening, agreement had been reached.

The weaponisation of finance

This is the first of a two-part FT series on the sanctions on Russia’s central bank and a new era of financial warfare. The article on Thursday will ask: will the international financial system ever be the same?

Yellen, who used to chair the US Federal Reserve, and Draghi, a former head of the European Central Bank, are veterans of a series of dramatic crises — from the 2008-09 financial collapse to the euro crisis. All the while, they have exuded calm and stability to nervous financial markets.

But in this case, the plan agreed by Yellen and Draghi to freeze a large part of Moscow’s $643bn of foreign currency reserves was something very different: they were effectively declaring financial war on Russia.

The stated intention of the sanctions is to significantly damage the Russian economy. Or as one senior US official put it later that Saturday night after the measures were announced, the sanctions would push the Russian currency “into freefall”.

This is a very new kind of war — the weaponisation of the US dollar and other western currencies to punish their adversaries.

It is an approach to conflict two decades in the making. As voters in the US have tired of military interventions and the so-called “endless wars”, financial warfare has partly filled the gap. In the absence of an obvious military or diplomatic option, sanctions — and increasingly financial sanctions — have become the national security policy of choice.

“This is full-on shock and awe,” says Juan Zarate, a former senior White House official who helped devise the financial sanctions America has developed over the past 20 years. “It’s about as aggressive an unplugging of the Russian financial and commercial system as you can imagine.”

The weaponisation of finance has profound implications for the future of international politics and economics. Many of the basic assumptions about the post cold war era are being turned on their head. Globalisation was once sold as a barrier to conflict, a web of dependencies that would bring former foes ever closer together. Instead, it has become a new battleground.

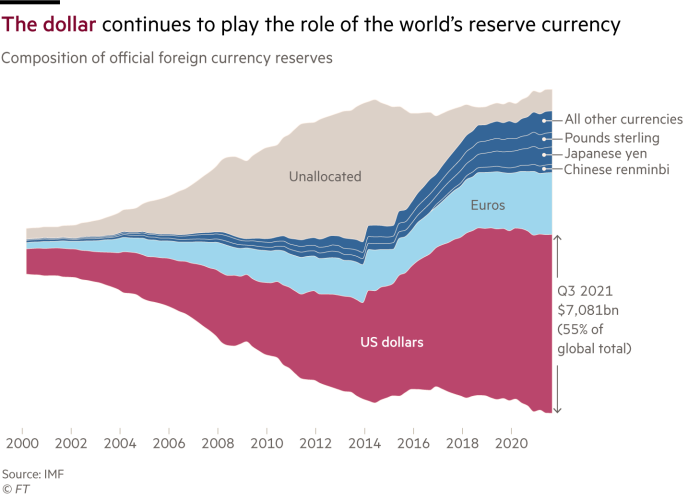

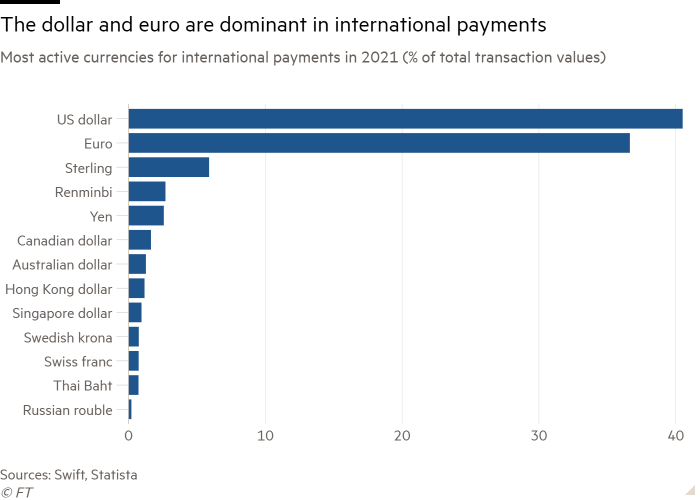

The potency of financial sanctions derives from the omnipresence of the US dollar. It is the most used currency for trade and financial transactions — with a US bank often involved. America’s capital markets are the deepest in the world, and US Treasury bonds act as a backstop to the global financial system.

As a result, it is very hard for financial institutions, central banks and even many companies to operate if they are cut off from the US dollar and the American financial system. Add in the euro, which is the second most held currency in central bank reserves, as well as sterling, the yen and the Swiss franc, and the impact of such sanctions is even more chilling.

The US has sanctioned central banks before — North Korea, Iran and Venezuela — but they were largely isolated from global commerce. The sanctions on Russia’s central bank are the first time this weapon has been used against a major economy and the first time as part of a war — especially a conflict involving one of the leading nuclear powers.

Of course, there are huge risks in such an approach. The central bank sanctions could prompt a backlash against the dollar’s dominance in global finance. In the five weeks since the measures were first imposed, the Russian rouble has recovered much of the ground it initially lost and officials in Moscow claim they will find ways around the sanctions.

Whatever the result, the moves to freeze Russia’s reserves mark a historic shift in the conduct of foreign policy. “These economic sanctions are a new kind of economic statecraft with the power to inflict damage that rivals military might,” US President Joe Biden said in a speech in Warsaw in late March. The measures were “sapping Russian strength, its ability to replenish its military, and its ability to project power”.

Global financial police

Like so much else in American life, the new era of financial warfare began on 9/11. In the aftermath of the 2001 terror attacks, the US invaded Afghanistan, moved on to Iraq to topple Saddam Hussein and used drones to kill alleged terrorists on three continents. But with much less scrutiny and fanfare, it also developed the powers to act as the global financial police.

Within weeks of the attacks on New York and the Pentagon, George W Bush pledged to “starve the terrorists of funding”. The Patriot Act, the controversial law that provided the basis for the Bush administration’s use of surveillance and indefinite detention, also gave the Treasury department the power to effectively cut off any financial institution involved in money laundering from the US financial system.

By coincidence, the first country to be threatened under this law was Ukraine, which the Treasury warned in 2002 risked having its banks compromised by Russian organised crime. Shortly after, Ukraine passed a new law to prevent money laundering.

Treasury officials also negotiated to gain access to data about suspected terrorists from Swift, the Belgium-based messaging system that is the switchboard for international financial transactions — the first step in an expanded network of intelligence on money moving around the world.

The financial toolkit used to go after al-Qaeda’s money was soon applied to a much bigger target — Iran and its nuclear programme.

Stuart Levey, who had been appointed as the Treasury’s first under-secretary of terrorism and financial intelligence, remembers hearing Bush complain that all the conventional trade sanctions on Iran had already been imposed, leaving the US without leverage. “I pulled my team together and said: ‘We haven’t begun to use these tools, let’s give him something he can use with Iran’,” he says.

The US sought to squeeze Iran’s access to the international financial system. Levey and other officials would visit European banks and quietly inform them about accounts with links to the Iranian regime. European governments hated that an American official was effectively telling their banks how to do business, but no one wanted to fall foul of the US Treasury.

During the Obama administration, when the White House was facing pressure to take military action against its nuclear installations, the US imposed sanctions on Iran’s central bank — the final stage in a campaign to strangle its economy.

Levey argues that financial sanctions not only put pressure on Iran to negotiate the 2015 deal on its nuclear programme but also cleared a path for this year’s action on Russia.

“On Iran, we were using machetes to cut down the path step by step, but now people are able to go down it very quickly,” he says. “Going after the central bank of a country like Russia is about as powerful a step as you can take in the category of financial sector sanctions.”

Central banks do not just print money and monitor the banking system, they can also provide a vital economic buffer in a crisis — defending a currency or paying for essential imports.

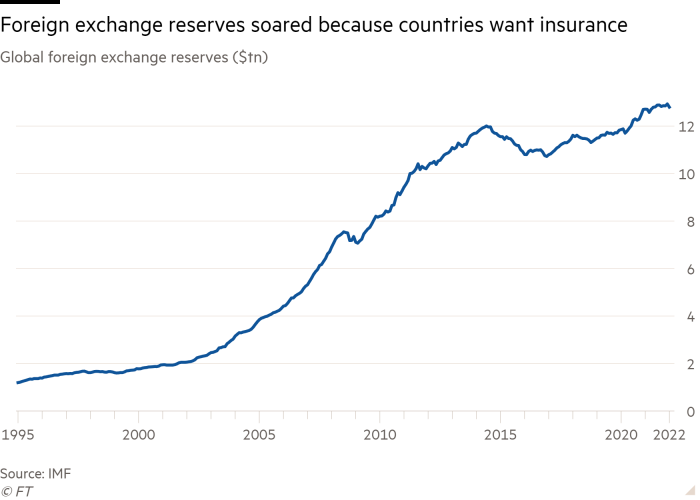

Russia’s reserves increased after its 2014 annexation of Crimea as it sought insurance against future US sanctions — earning the term “Fortress Russia”. China’s large holdings of US Treasury bonds were once seen as a potential source of geopolitical leverage. “How do you deal toughly with your banker?” then secretary of state Hillary Clinton asked in 2009.

But the western sanctions on Russia’s central bank have undercut its ability to support the economy. According to the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, a central bank research and advisory group, around two-thirds of Russia’s reserves are likely to have been neutralised.

“The action against the central bank is rather like if you have savings to be used in case of emergency and when the emergency arrives the bank says you can’t take them out,” says a senior European economic policy official.

A revived transatlantic alliance

There is an irony behind a joint package of American and EU financial sanctions: European leaders have spent much of the past five decades criticising the outsized influence of the US currency.

One of the striking features of the war in Ukraine is the way Europe has worked so closely with the US. Sanctions planning began in November when western intelligence picked up strong evidence that Vladimir Putin’s forces were building up along the Ukrainian border.

Biden asked Yellen to draw up plans for what measures could be taken to respond to an invasion. From that moment the US began coordinating with the EU, UK and others. A senior state department official says that between then and the February 24 invasion, top Biden administration officials spent “an average of 10 to 15 hours a week on secure calls or video conferences with the EU and member states” to co-ordinate the sanctions.

In Washington, the sanctions plans were led by Daleep Singh, a former New York Fed official who is now deputy national security adviser for international economics at the White House, and Wally Adeyemo, a former BlackRock executive serving as deputy Treasury secretary. Both had worked in the Obama administration when the US and Europe had disagreed about how to respond to Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

The EU was also desperate to avoid a more recent embarrassing precedent regarding Belarus sanctions, which ended up much weaker as countries sought carve-outs for their industries. So in a departure from previous practices, the EU effort was co-ordinated directly from von der Leyen’s office through Bjoern Seibert, her chief of staff.

“Seibert was key, he was the only one having the overview on the EU side and in constant contact with the US on this,” recalls an EU diplomat.

A senior state department official says Germany’s decision to scrap the Nord Stream 2 pipeline after the invasion was crucial in bringing hesitant Europeans along. It was “a very important signal to other Europeans that sacred cows would have to be sacrificed,” says the official.

The other central figure was Canada’s finance minister Chrystia Freeland, who is of Ukrainian descent and has been in close contact with officials in Kyiv. Just a few hours after Russian tanks started rolling into Ukraine, Freeland sent a written proposal to both the US Treasury and the state department with a specific plan to punish the Russian central bank, a western official says. That day, Justin Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister, raised the idea at a G7 leaders’ emergency summit. And Freeland issued an emotional message to the Ukrainian community in Canada. “Now is the time to remember,” she said, before switching to Ukrainian, “Ukraine is not yet dead.”

The threat of economic pain may not have deterred Putin from invading, but western leaders believe the financial sanctions that have been put in place since the invasion are evidence of a revitalised transatlantic alliance — and a rebuke to the idea that democracies are too slow and hesitant.

“We have never had in the history of the European Union such close contacts with the Americans on a security issue as we have now — it’s really unprecedented,” says one senior EU official.

Draghi takes the initiative

In the end, the move against Russia’s central bank was the product of 72 hours of intensive diplomacy.

With Russia seemingly intent on a rapid occupation of Ukraine, emotions were running high. During a video call with EU leaders on February 24, the day the invasion began, Volodymyr Zelensky, the Ukrainian president, warned: “I might not see you again because I’m next on the list.”

The idea had not been the priority of prewar planning, which focused more on which Russian banks to cut off from Swift. But the ferocity of Russia’s invasion brought the most aggressive sanctions options to the fore.

“The horror of Russia’s unacceptable, unjustified, and unlawful invasion of Ukraine and targeting of civilians — that really unlocked our ability to take further steps,” says one senior state department official.

In Europe, it was Draghi who pushed the idea of sanctioning the central bank at the emergency EU summit on the night of the invasion. Italy, a big importer of Russian gas, had often been hesitant in the past about sanctions. But the Italian leader argued that Russia’s stockpile of reserves could be used to cushion the blow of other sanctions, according to one EU official.

“To counter that . . . you need to freeze the assets,” the official says.

The last-minute nature of discussions was critical to ensure Moscow was caught off-guard: given enough notice, Moscow could have started moving some of its reserves into other currencies. An EU official says that given reports Moscow had started placing orders, the measures needed to be ready by the time the markets opened on Monday so that banks would not process any trades.

“We took the Russians by surprise — they didn’t pick up on it until too late,” the official says.

According to Adeyemo at the US Treasury: “We were in a place where we knew they really couldn’t find another convertible currency that they could use and try to subvert this.”

The last-minute talks caught some western allies off guard — forcing them to rush to implement the measures in time. In the UK, they triggered a frantic weekend effort by British Treasury officials to finalise details before the markets opened in London at 7am on Monday. Chancellor Rishi Sunak communicated by WhatsApp with officials through the night, with the work only concluding at 4am.

No clear political strategy

Yet if the western response has been defined by unity, there are already signs of potential faultlines — especially given the new claims about war crimes, which have prompted calls for further sanctions.

Western governments have not defined what Russia would need to do for sanctions to be lifted, leaving some of the difficult questions about the political strategy for a later date. Is the objective to inflict short-term pain on Russia to inhibit the war effort or long-term containment?

Even when they work, sanctions take a long time to have an impact. However, the economic pain from the crisis is being unevenly felt, with Europe suffering a much bigger blow than the US.

Europe has so far been reluctant to impose an oil and gas embargo, given the bloc’s high dependence on Russian energy imports. But since the atrocities allegedly perpetrated by Russian soldiers in the suburbs of Kyiv have been revealed, a fresh round of EU sanctions was announced on Tuesday that will include a ban on Russian coal imports and, at a later stage, possibly also oil. A decision among the 27 capitals is expected later this week.

The other key factor is whether the west can win the narrative contest over sanctions — both in Russia and in the rest of the world.

Speaking in 2019, Singh, the White House official, admitted that sanctions imposed on Russia after Crimea were not as effective as hoped because Russian propaganda succeeded in blaming the west for economic problems.

“Our inability to counter Putin’s scapegoating,” he told Congress, “gave the regime far more staying power than it would have enjoyed otherwise.”

In the coming weeks and months, Putin will try to convince a Russian population undergoing economic hardship that it is the victim, not the aggressor.

To China, India, Brazil and the other countries which might potentially help him evade the western sanctions, Putin will pose a deeper question about the role of the US dollar in the global economy: can you still trust America?

Additional reporting by Dan Dombey in Madrid, Colby Smith in Washington, George Parker in London, Robin Wigglesworth in Oslo

Are you personally affected by the War in Ukraine? We want to hear from you

Are you from Ukraine? Do you have friends and family in or from Ukraine whose lives have been upended? Or perhaps you’re doing something to help those individuals, such as fundraising or housing people in your own homes. We want to hear from you. Tell us via a short survey.