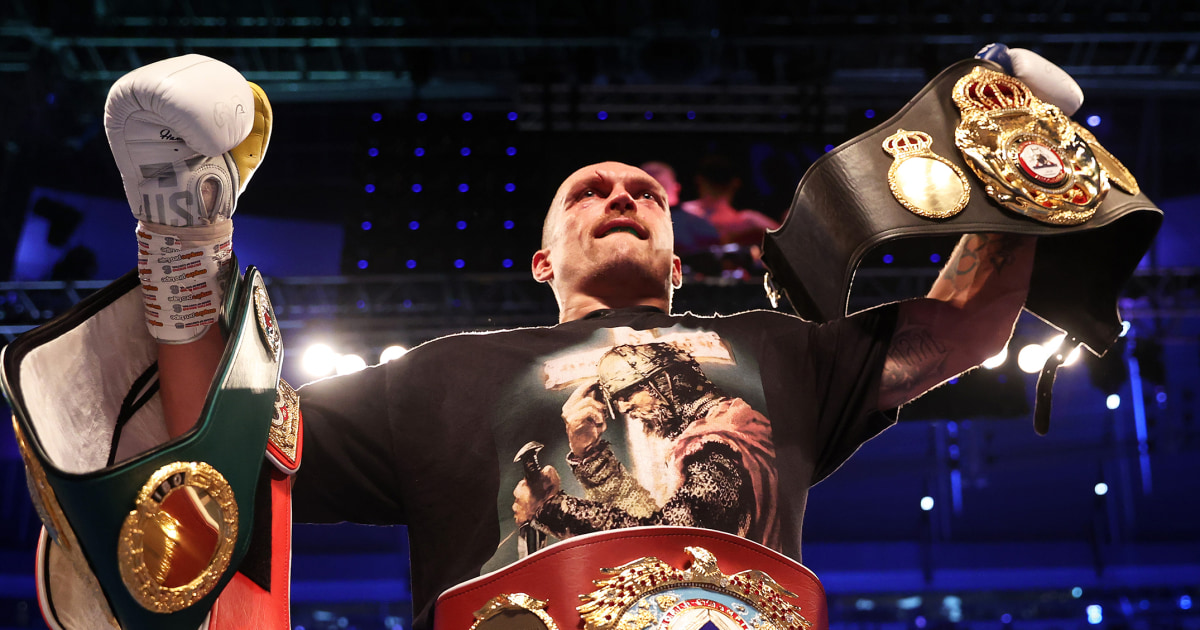

World heavyweight boxing champion Oleksandr Usyk should be training for his biggest fight to date — a defense of his titles against Britain’s Anthony Joshua and a multimillion-dollar payday.

Instead he is hunkered down in a Kyiv bomb shelter, having returned to his homeland from the United Kingdom to enlist in the Ukrainian capital’s territorial defense unit.

“What do you mean why?” Usyk asked, looking slightly baffled when asked Wednesday why he signed up by CNN. “It is my duty to fight, to defend my home, my family.”

The highly anticipated rematch against Joshua, whom he stripped of three of the four major titles in boxing’s blue riband division in September, will have to wait. A date had not been set; his highest payday to date would likely have been in the spring or the summer.

Instead, as Russian forces continue to attack the city and their invasion of Ukraine enters its third week, Usyk is preparing for a different type of fight, one that is considerably more deadly.

Usyk, alongside Vasiliy Lomachenko and brothers Wladimir and Vitali Klitschko, is a product of Ukraine’s world-renowned national boxing system, which has trained some of the world’s most technically dazzling fighters of this generation.

Lomachenko, a three-weight world champion whom many experts regard as the best pound-for-pound boxer in the world, also traveled from Greece back to his home city, Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi in southwest Ukraine, which is coming under increasing threat after Russian forces captured Kherson, around 180 miles away.

He has consistently stressed his desire for peace but said he had nonetheless signed up with a territorial defense unit.

Yaroslav Amosov, a mixed martial arts fighter and the current Bellator MMA welterweight champion, also returned home to fight, he said in an Instagram video late last month.

Their actions have not gone unnoticed, and their worldwide fame and millions of social media followers have allowed them to galvanize support for Ukraine and reach audiences that the country’s traditional political leaders could never hope to.

Mike Tyson, whose adoptive mother immigrated to the U.S. from Ukraine, was recorded Monday telling a group of Russian reporters to “get out” of the country.

And Ukrainian boxers from gyms around the world have expressed their outrage in videos posted to social media, typically signing off with the shout of “Slava Ukraini,” or “Glory to Ukraine.”

“It’s really inspiring to see such famous people ready to protect our homeland with weapons in their hands,” Ukrainian sports reporter Igor Nitsak said by telephone Wednesday.

“They had many chances to flee the country, but they stayed. I think it’s pure courage,” said Nitsak, 37, who fled Kyiv to the city of Zhytomyr with his wife, Lyudmyla, 37, and their sons — Roman, 10, and Andriy, 2 — on the day Russian forces invaded.

He added that Vitali Klitschko, the mayor of Kyiv, and his brother, Wladimir, both former heavyweight boxing champions and the sons of a Soviet major general, had “always been the embodiment of courage for our people.”

Vitali Klitschko, who has been rallying his people and posting video messages to social media about the situation in Kyiv, was “radiating with strong belief that we will actually win in the end,” Nitsak said.

He said Usyk’s decision to fight was notable because the former undisputed world cruiserweight champion is not universally loved in Ukraine, where he has previously been criticized for referring to Russians and Ukrainians as “one people.” The trope has been used by President Vladimir Putin, who called them both Russian.

Usyk, who hails from Simferopol in annexed Crimea, was also criticized for his appearance in the Russian film “Hello, Brother, Christ Is Risen.”

The fact that he and the other fighters have huge followings in both the West and in Russia is important, Nitsak said.

“Ukraine is fighting on two fronts, military and informational,” he said, adding that some of his relatives in Russia had believed the Kremlin’s propaganda and refused to believe their country had launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, even when he told them he was hiding from shelling in a basement with his family.

Athletes can cross partisan lines, said to Charlie Baker, a professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science. “People are more likely to pay attention to a sporting figure than they would a politician,” he said.

“Russians who are sympathetic to a Ukrainian boxer, who have cheered him in the past, would at least humanize them,” he said. “That’s a really important thing in this conflict.”

Athletes on social media talk not just about sports but also other parts of their lives, like their partners or their children, and that helps them become more human in the eyes of their followers, he said.

However, Baker cautioned that social media is used to spread false information, “so people will be suspicious of things on there that don’t match the official version of events.”

For Nitsak, however, the boxers were “a powerful weapon,” because, he said, “they will help open the eyes of ordinary Russian people.”